The River Wild

KEEPING THE RIVER WILD

For more than 50 years, the Steamboaters have been dedicated to preserving and protecting the wild beauty of the world-famous North Umpqua River and its native inhabitants.

Story by Geoff Shipley Photos by Steven Yochum

Cover Photo by Robin Loznak

Down through the forested slopes of eastern Douglas County’s Calapooya Mountains, the North Umpqua River cuts a stunning blue-green swath from its headwaters at Maidu Lake high in the Cascades before joining its southern sister stream near Roseburg to form the main stem of the Umpqua River.

Visitors to a 30-some-mile stretch in the North Umpqua River’s upper course dedicated to fly fishing, sightseeing and recreation find frothing cataracts and riffles giving way to deep, turquoise-colored pools and placid-looking runs where foam lines and bursting bubbles lie strewn across the surface in a constantly changing recitation of nature’s poetry.

Stripped and bare tree trunks lay precariously stranded on dark, truck-sized basalt boulders, waiting for winter floods to set them free while their living cousins—hemlocks, firs, cedars, maples—stand green and full streamside. The river’s banks and uplands host osprey and elk and ground squirrels and butterflies and beetles and spiders and all the rest making a proper home, just as they have for ages.

It’s little wonder why this stretch received National Wild and Scenic River designation in 1988.

“My wife and I were kidnapped by the North Umpqua,” says Tim Goforth, with a smile but also with a touch of sincerity in his voice as he explains how he and his wife came to call the river home.

The happy abduction happened in 1980 and now Goforth, president of the Steamboaters, an organization dedicated to the preservation and protection of the North Umpqua’s unique natural gifts and the promotion of the tradition of fly fishing, has enjoyed a relationship with the river that goes back nearly four decades.

“We spent all our free time, all the free vacations we could get down here,” says Goforth.

And when retirement came, so did a home near the river so he and his wife could spend as much time with it and their beloved steelhead as possible.

“I was talking to my wife the other day and she said, ‘Well, Tim, don’t you know, the steelhead are our religion?’ That pretty much sums it up.”

The North Umpqua River is known for capturing the imagination and, perhaps only outdone by the sheer beauty and untamed character of the place and the Nationa l Scenic Byway that careens beside it, the large silver-sided ocean-going trout often plays a central role in captivating visitors.

Popular writers in the 1920s and 30s such as Lawrence Mott and Zane Grey brought tales of almost-mythical fishing for the river’s native wild steelhead to a national audience. Frank Moore has become an icon of conservation and a living legend in Oregon and beyond, a journey inseparably influenced by his time observing and connecting with the North Umpqua basin and its wild residents.

With more than 150 members (some from as far away as Germany, Belgium and Japan), the Steamboaters— founded in 1966 and named for the crucial steelhead spawning habitat of the Steamboat Creek tributary—play an important and much-needed role in protecting the river’s resources for anglers, recreationists, local residents and visitors. Member- and volunteer-driven efforts extend into science, public education, community outreach, fundraising and regulations.

“We have some outstanding people who have been involved with developing regulations and doing science studies all up and down the West Coast and are incredibly knowledgeable, at a professional level and as top amateurs,” says Goforth. “Those are the people I count on. I could never do any of this by myself.”

Outside of just its members and volunteers, partnering, collaborating and cooperating with agencies and groups of all kinds has long been a hallmark of the Steamboaters organization.

There’s the annual funding help they provide to the Glide Wildflower Show, one of the largest on the West Coast. It’s the perfect way to support a cherished community event while educating visitors from all over the United States about the splendor, exceptional natural resources and the crucial need to protect the North Umpqua River and the entire watershed.

The North Umpqua Foundation (TNUF), founded in 1983, shares many of the same goals as the Steamboaters and the two organizations work closely on many projects.

“While our groups might focus on different areas,” says Becky McRae, president of TNUF, “the common thread is always the protection of the river, its fish and the habitat surrounding the river.”

The North Umpqua River is known for capturing the imagination, and the large silver-sided, ocean-going trout that call it home often play a central role in captivating visitors.

Donations from the Steamboaters help fund an onsite caretaker at Big Bend Pool on Steamboat Creek, a program run continuously since 1992 by TNUF and known as FishWatch. Wild summer-run steelhead congregate and stage in Big Bend Pool with spawning on their minds, waiting for rains to swell the creek so they can head further upstream. Dozens of fish can often be seen hovering in plain sight. Before FishWatch and the dedication of custodians such as Lee Spencer and Ed Kikumoto, the unsavory (or simply the uneducated) had been known to poach the pool—to destructive effect on the wild fish stocks.

Steamboater donations also help to fund scholarships for Roseburg-area residents through TNUF, a thriving program that recently inspired a private donor to offer a $25,000 match on scholarship funds donated through November of this year.

Another important collaboration, one miles downstream from Deadline Falls and the start of the North Umpqua River’s fly-fishing-only water, hopes to shine a light on the health of the river by collecting valuable scientific data regarding the quantity and movement of not just wild and hatchery-reared steelhead but also salmon, rainbow and cutthroat trout and even the occasional Pacific lamprey.

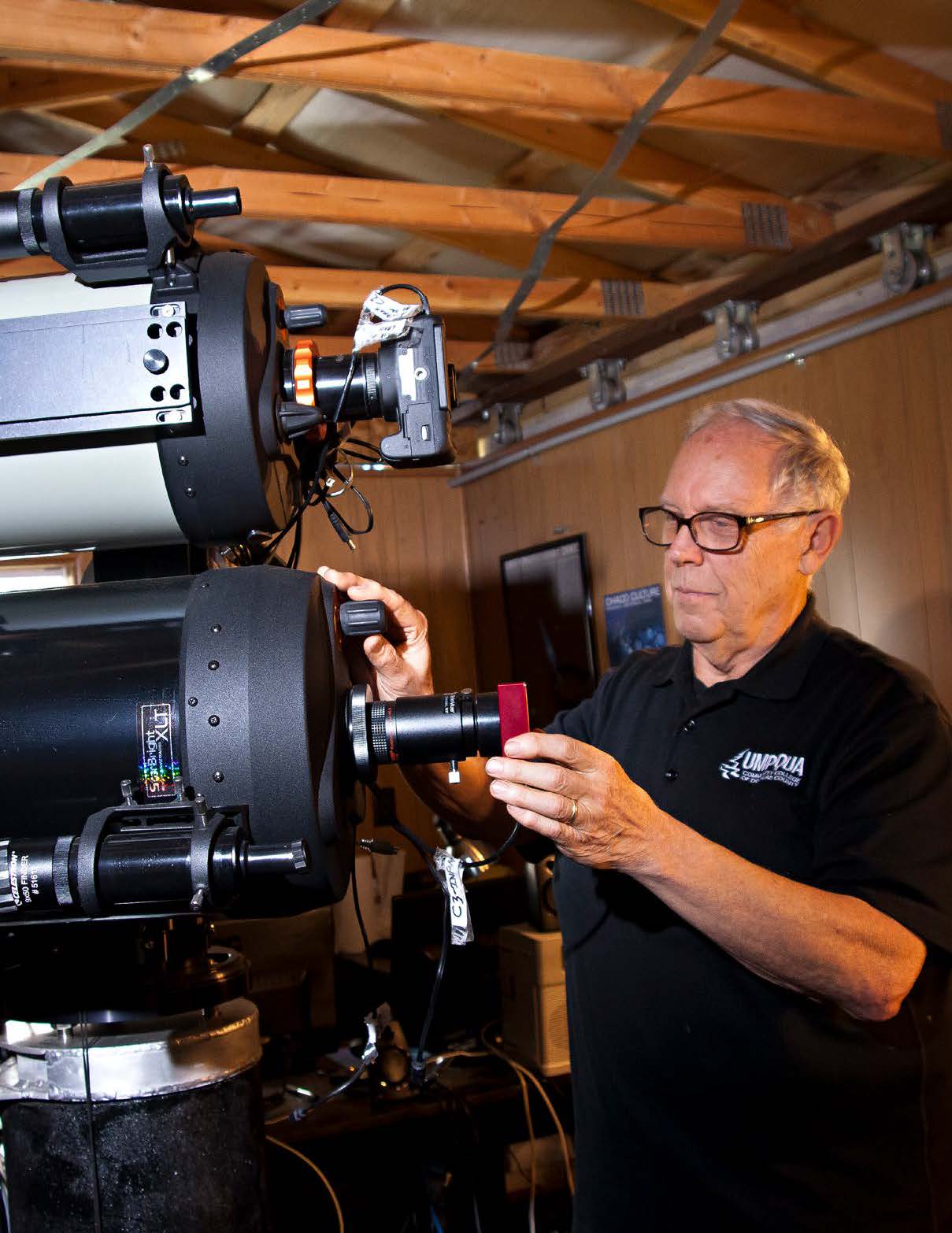

The Steamboaters, working in partnership with Trout Unlimited, TNUF, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), Oregon State University’s fisheries program and under a grant from the Flyfishers’ Club of Oregon, are conducting fish counting work at Winchester Dam on the North Umpqua River near Winchester, Oregon, a project now in its second season.

While ODFW does count anadromous fish (those that swim upriver from the sea to spawn) at Winchester Dam, funding constraints mean a system that relies on collecting data in “snapshots” and then extrapolating that information mathematically to days, weeks or months. But thanks to the funding grant, project volunteers and staff are able to use a software program called “FishTick” to capture every fish that passes in front of video monitoring equipment in real-time for later analysis and study. The result is refined, highly accurate fish-count data.

Dean Finnerty, Trout Unlimited’s Northwest director of the Sportsmen’s Conservation Project and manager of the Wild Steelhead Initiative, explains that while Oregonians expect effective management of their resources and fisheries, it’s difficult for agencies such as ODFW to balance needs when they struggle to get the strong scientific data needed to make smart watershed and recreation decisions. Efforts like the FishTick project and other citizen-science initiatives supported by member and volunteer organizations like the Steamboaters can play a crucial role in helping to fill the knowledge gap.

It’s also helping prepare the next generation of resource managers and biologists by using technology to overcome funding and staffing constraints.

“Working with cutting-edge technology and helping these graduate students from Oregon State University get a leg up in their careers is tremendously rewarding,” says Finnerty.

He and others hope to eventually share the fish-count data with the public through the Steamboaters’ website, ideally on a week-to-week basis. The idea is simply to collect and publically share information that shines a light on the health and vitality of the North Umpqua River and the challenges the watershed and its wild residents face.

“If you follow the anadromous fish situation on the West Coast, it’s gone way downhill,” says Goforth. “We’re having a terrible season this year.”

What’s causing relatively poor returns of steelhead and salmon and other anadromous species, including sea-run cutthroat trout and Pacific lamprey? Goforth points to a host of potential reasons.

Poor ocean conditions and the presence of what marine biologists termed “The Blob” of unusually warm, nutrient-poor water that’s affected the West Coast. A string of relatively low snow-pack and low-water years means a shallower, warmer river that increases the potential for migrating fish to be stranded or have their patterns disrupted.

Specific to steelhead, there are also populations of hatchery-reared strains that science is showing weaken and diminish the natural genetic vitality of wild native steelhead stocks when the two varieties interbreed. And as the water warms, the hatchery fish in the North Umpqua River system that might normally turn off at Rock Creek near Idleyld Park instead head upriver—and into a wild steelhead refuge eons old—in search of cooler water suitable for spawning. Interbreeding is a natural consequence.

Determining to what extent—exactly—these complex challenges, and others, are having on wild steelhead and other fish and their natural breeding grounds on rivers like the North Umpqua, however, is why long-term partnerships and collaboration with a host of organizations and interests is so important.

“It’s a constant discussion,” says Goforth. “It takes time.”

For anglers who visit the North Umpqua River in hopes of hooking and briefly subduing one of its wild finned inhabitants, the fishing experience can be quite distinct from other popular steelhead rivers throughout the Western U.S. and Canada.

People who monopolize a fishing hole, crowd other anglers, exhibit poor fish handling or generally make a nuisance of themselves might experience, not a high-brow lecture, but some simple, friendly suggestions from a Steamboater about how thousands of anglers have peacefully and happily enjoyed some of the best fishing of their lives on the North Umpqua River by following some plain guidelines fostered around courtesy and respect.

The etiquette sets the river apart from other waterways where “combat fishing” and the accompanying conflicts are all too common. For anglers, such defined customs help protect the fish while serving as an important tradition for preserving the unique experience of challenging the North Umpqua River.

“When I started fishing down here I watched a lot of guys who are no longer alive and I watched how they did stuff and I talked to them about how they did stuff and why they did stuff,” says Goforth. “They weren’t always forthcoming about where to go, but they’d share their knowledge and the etiquette was always a huge thing.”

For the Steamboaters, holding the native wild steelhead as its icon is about more than pursuing a wily and mysterious fish in an impossibly beautiful place with rod and fly. It’s also a natural consequence of the species’ tough character and resilient nature.

“Steelhead are the Olympic athletes of fish,” explains Goforth.

Navigating from steep, tiny tributaries to the sea, steelhead spend a few years there feeding and maturing before returning to their birth streams to spawn. Unlike salmon, many steelhead survive spawning and return to the ocean to repeat the cycle the second time.

Through their journey, they find a way to withstand and conquer the immense expanse of the Pacific Ocean, powerful rivers, watchful predators and seemingly impassable waterfalls while traveling hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles to their home streams ranging from Alaska to California and as far inland as Idaho.

Remarkable endurance athletes indeed.

And because of that propensity to overcome obstacles, the steelhead are a crucially important indicator species for what’s happening ecologically in the North Umpqua River, the Umpqua River basin and the Pacific Northwest. How well the steelhead are doing is an indication of just how well we’re taking care of things, an idea the Steamboaters have been sharing for more than 50 years by promoting and encouraging the preservation of a special place that embodies Oregon’s heritage, its good fortune and, hopefully, its future.

North Umpqua River etiquette

A true sportsman goes fishing not only to catch fish, but also to enjoy God’s gifts of clear sweet water, the forest, and all the creatures that live in them.

An ethical flyfisher is considerate of others who want to enjoy the North Umpqua River by:

Allowing the flyfisher already at a pool to fish through it without interference.

Not entering the river close below or across from anyone fishing, nor casting near water being fished by another.

Sharing the water by fishing through the pool. After a reasonable time on the pool, a flyfisher should invite the waiting person to join in fishing the pool, allow the other person to pass through and fish the water below, or vacate the pool for the other person.

Gladly releasing wild fish.

Being alert to the presence of spawning fish or redds, and giving a wide berth to both.

(Originally written in 1959 by Ted Novis, one of the Steamboaters’ founders)

How To Get Involved

For more information or to get involved protecting and preserving the North Umpqua River, visit:

●The Steamboaters – steamboaters.org

●The North Umpqua Foundation – northumpqua.org

●Wild Steelhead Initiative/Wild Steelheaders Unite – wildsteelheaders.org

●Trout Unlimited (local chapter) – theredsides.org

●Trout Unlimited (national) – tu.org